- Home

- Sue Corbett

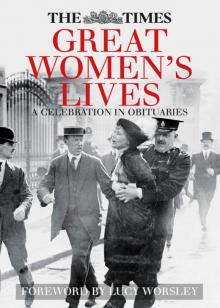

The Times Great Women's Lives

The Times Great Women's Lives Read online

CONTENTS

Title

Foreword by Lucy Worsley

Introduction by Sue Corbett

Mary Somerville

Harriet Martineau

George Eliot

Jenny Lind

Frances Mary Buss

Christina Rossetti

Clara Schumann

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Rosa Bonheur

Dorothea Beale

Baroness Burdett-Coutts

Josephine Butler

Florence Nightingale

Octavia Hill

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson

Lady Randolph Churchill

Emily Davies

Sarah Bernhardt

Gertrude Bell

Emmeline Pankhurst

Dame Ellen Terry

Dame Millicent Fawcett

Anna Pavlova

Dame Nellie Melba

Gertrude Jekyll

Marie Curie

Amelia Earhart

Lilian Baylis

Suzanne Lenglen

Amy Johnson

Virginia Woolf

Ellen Wilkinson

Maria Montessori

Eva Perón

Margaret Bondfield

Dame Caroline Haslett

Dorothy L. Sayers

Dame Christabel Pankhurst

Rosalind Franklin

Marie Stopes

Countess Mountbatten of Burma

Sylvia Pankhurst

Marilyn Monroe

Eleanor Roosevelt

Nancy, Viscountess Astor

Dame Myra Hess

Enid Blyton

Professor Dorothy Garrod

Dame Adeline Genée

Janis Joplin

“Coco” Chanel

Dame Kathleen Lonsdale

Dame Barbara Hepworth

Dame Agatha Christie

Dame Sybil Thorndike

Dame Edith Evans

Cecil Woodham-Smith

Joan Crawford

Maria Callas

Nadia Boulanger

Golda Meir

Dame Gracie Fields

Dame Rebecca West

Lillian Hellman

Indira Gandhi

Laura Ashley

Simone de Beauvoir

Beryl Markham

Jacqueline du Pré

Bette Davis

Professor Daphne Jackson

Dame Margot Fonteyn

Eileen Joyce

Dame Peggy Ashcroft

Marlene Dietrich

Elizabeth David

Barbara McClintock

Marian Anderson

Dame Freya Stark

Tatiana Nikolayeva

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Dorothy Hodgkin

Odette Hallowes

Ginger Rogers

Alison Hargreaves

Pat Smythe

Diana, Princess of Wales

Mother Teresa

Joyce Wethered

Martha Gellhorn

Dame Iris Murdoch

Dusty Springfield

Baroness Ryder of Warsaw

Elizabeth Anscombe

Dame Ninette de Valois

Katharine Graham

Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother

Baroness Castle of Blackburn

Joan Littlewood

Elizabeth, Countess of Longford

Katharine Hepburn

Gertrude Ederle

Dame Alicia Markova

Dame Miriam Rothschild

Dame Moura Lympany

Dame Cicely Saunders

Rosa Parks

Dame Muriel Spark

Dame Elisabeth Schwarzkopf

Jeane Kirkpatrick

Dame Anne McLaren

Benazir Bhutto

Helen Suzman

Dame Joan Sutherland

Dame Elizabeth Taylor

Brigadier Anne Field

Amy Winehouse

Wangari Maathai

Shirley Becke

Marie Colvin

Baroness Thatcher

Mavis Batey

Doris Lessing

Shirley Temple

Alice Herz-Sommer

Copyright

FOREWORD

A GIRL’S GUIDE TO GREATNESS

by Lucy Worsley

What is it that makes a woman great? The answer, as revealed in these 125 obituaries from The Times newspaper, has changed over time in ways that can’t fail to fascinate.

One of the encouraging themes of the collection is that scientists, writers, performers, politicians and campaigners are not born, nor are they made. They make themselves. And a soaring rise from a humble background certainly makes for a good obituary. We learn that Eva Perón, First Lady of Argentina, was a “Cinderella in real life” to the young people she inspired, and I was tickled to discover that the Labour politician Barbara Castle began her career selling crystallised fruit in a Manchester department store while dressed as “Little Nell”. A tragic death cutting off early promise also makes for a striking story: aviator Amy Johnson at 37 in 1941; troubled singer Amy Winehouse at 27 in 2011; mountaineer Alison Hargreaves on K2 at only 33 in 1995.

It might not surprise the cynical to discover how important good looks have been to the greatness of women, or at least so it has been in the eyes of their obituarists. The suffragette Christabel Pankhurst, we hear, was “a most attractive young woman with fresh colouring, delicate features, and a mass of soft brown hair”. Striking looks, constantly mentioned, sometimes had unusual consequences: the blue-eyed Swedish soprano Jenny Lind, for instance, gave her name to a breed of potatoes with blue specks on their skins. The only woman in the whole collection whose looks are disparaged seems to be George Eliot, notable for “her resemblance to Savonarola”. With all this emphasis on appearance, I don’t blame Joan Crawford in the slightest for keeping her birthdate so secret that The Times was only able to give her age at death as falling somewhere in the range between 69 and 76.

And being nice has been just as good as being skilled at what you do. It’s a strain that persists surprisingly, and depressingly, far through the collection’s chronology. Among the earlier subjects, Christina Rossetti produced writing that manifested “purity of thought”, while it was the happy lot of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first female doctor to qualify in England, to “emerge not only successful but still a ‘womanly woman’ ”. But when you reach obituaries from the late twentieth century, the convention of the lovely lady persists in ways that read almost like a parody: the crystallographer Dame Kathleen Lonsdale was described in 1971 as looking “in no way unfeminine”, despite having “golliwog” hair, and is praised for having “made herself a neat hat for a few shillings” for a visit to Buckingham Palace. “The most successful princesses in history,” claims the obituary of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1997, “have been those who loved children and cared for the sick.” Not exactly an uncontestable statement.

Because of the same convention of niceness, the early obituaries sometimes have difficulty in expressing what they’re talking about. Philanthropist Baroness Burdett-Coutts founded a “Home” at Shepherd’s Bush for single mothers, which was euphemistically described as “one of the earliest practical attempts to reclaim women who had lost their characters”. It’s actually quite hard to puzzle out exactly what Josephine Butler did, so obliquely is it described in her obituary. She’s hailed as “a woman of extreme delicacy and refinement of mind, with a horror… of contact with vice”. In fact she campaigned against the Contagious Diseases Act, which decreed that, on the mere say-so of a policeman, a woman could have her private parts inspected for venereal disease and be impr

isoned if she refused.

If you can’t be nice, however, be difficult. This theme emerges as the decades pass. Here Bette Davis excelled (“Nobody’s as good as Bette when she’s bad”), while the French actress Sarah Bernhardt slept in a coffin and killed her pet alligator by giving it too much champagne. And being angry works, too. Coco Chanel, inventor of the strappy sandal and the cardigan jacket, had a comeback in the 1950s inspired by the “irritation of seeing Paris fashion taken over by men designers”. Pat Smythe, international showjumper, might have been equally chagrined at being given a silver cigar box for winning a competition with the words: “Sorry about this, we were not expecting a woman rider to be as good as you.” Being uncommunicative seems an excellent means of finding the time to get on with being great. Elizabeth David, the cookery writer, instructed directory enquiries not to tell anyone her number, “under any circumstances, even in case of death”, while Barbara McClintock, Nobel Prize-winning scientist, said that “anyone who wanted to talk to her… could write a letter”.

Being on the left politically will definitely help you achieve greatness, because it puts you in the vanguard of struggle and change. We have “Red Ellen”, the Labour MP Ellen Wilkinson (following the rules about good looks above, she nevertheless had an “oddly picturesque person”) and “the Red Dame”, actress and CND supporter Peggy Ashcroft. Movingly, the former “Little Nell”, Barbara Castle, gets a standing ovation at the Labour Party Conference at the age of 86 even before having reached the microphone.

Most of all, though, it’s courage that’s celebrated here. Courage is what links Emmeline Pankhurst, campaigner for votes for women, who was “of the stuff of which martyrs are made”, to Odette Hallowes, who had her toenails pulled out during the war for her Resistance work. She shares it too with Marian Anderson, the first black singer to appear at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Refused tuition at a Philadelphia music school on the grounds that “we don’t take coloured”, Anderson reportedly trembled when she first stood on the stage of the Met. In her own words, though, it was worth it: “My mission is to leave behind me a kind of impression that will make it easier for those who follow.”

Well, all of these women have done this wonderfully well – even the ones with messy hair.

INTRODUCTION

by Sue Corbett

The 125 Times obituaries of great women in this volume had their genesis in the second issue of the paper, on Monday, January 3, 1785. The Times started life (as the Daily Universal Register) on Saturday, January 1, 1785, without any obituaries as the modern reader would understand the word. There were, instead, death notices, just two, very brief. By the following Monday, the number had doubled to four, with the addition, this time, of a dash of human interest. Two of the deceased were described as Mrs Alice Hermen, 93, a “native of Hanover and nurse to the late Prince Frederic”, and Mrs Margaret Scurral, who had “retained all her faculties (sight only excepted) till within a fortnight of her death” at the even more astonishing age, for that time, of 108.

These two intriguing little Georgian snippets offered a small foretaste of the first golden age of Times obituaries, which still lay decades away in the Victorian era (at the conclusion of which the paper would devote a 49,741-word obituary to Queen Victoria and her epoch). Meanwhile, lengthier obituaries did begin to appear, but haphazardly, so that in 1802 a Lord Chief Justice would receive upwards of 300 words, but in 1822 the death of Percy Bysshe Shelley received no attention whatsoever. Again, in 1825 the Earl of Carlisle’s death was deemed worthy of an obituary of 327 words, even though the piece itself acknowledged that his lordship “never attained any great distinction as a politician, a legislator, an author, or a man of talent”, while the novelist Lady Caroline Lamb’s death three years later was marked by just 125 words that defined her almost entirely in terms of the men whose daughter, sister, wife and daughter-in-law she had been.

A more orderly approach was imposed by John Thadeus Delane, Times editor from 1841 to 1877, who instituted the practice, which survives today, of preparing detailed, authoritative obituaries of the more important and influential personalities of the day while they are still alive. He oversaw the new regime himself because there would be no Times obituaries editor as such until the 1920s. And so, when the hero of Waterloo died on September 14, 1852, it was Delane who ordained that, in the paper the following day, “Wellington’s death will be the only topic.” Obituaries set in train by Delane were often very long, but none surpassed the wordage allotted the Iron Duke. Under the heading, “Death of the Duke of Wellington”, the obituary ran to 30,674 words on September 15, and a further 16,013 the next day.

Delane’s hand can also be seen in The Times’s lengthy tribute to Queen Victoria on January 23, 1901. Although her death the evening before occurred nearly a quarter of a century after he had retired, it is inconceivable, given the obituary’s length and the myriad topics it covered, that Delane wouldn’t, while still in office, have commissioned an obituary to be updated as necessary.

Delane was not, however, in the habit of handing out very many column inches to other female notables of the time (of whom there were comparatively very few, of course, most professions being closed to women). The composer Fanny Mendelssohn’s death in May 1847, for example, passed completely unnoticed in The Times. Her name did not even feature in her beloved brother Felix’s 989-word obituary in the paper when he died six months afterwards.

And the paper’s only acknowledgment of Gothic novelist Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, author of Frankenstein, when she died in February 1851, was to print a 21-word death notice, misspelling Wollstonecraft and simply describing her as “widow of the late Percy Bysshe Shelley, aged 53”.

Charlotte Brontë’s obituary in 1855, borrowed by The Times from the Manchester Guardian, amounted to just 86 words and Brontë’s biographer, the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell, was given only 207 words when she died in 1865 – these, too, reprinted from another publication, this time The Globe. Delane’s reforms were clearly not yet all they might have been.

It is the 1872 obituary of the scientist and mathematician Mary Somerville (pp. 16-18) that marks a new deal for women. The first of the obituaries of prominent women reproduced in this volume, it is detailed, authoritative and, at 1,240 words, remarkably long for a woman’s obituary of that era. It does lack the human interest that a modern obituarist strives for – the “telling anecdotes” and domestic details – but this was provided two days later when a letter to the editor was published from a friend of the great woman (clearly a forerunner of contributors to the modern Times’s “Lives Remembered” postscripts to published obits). The anonymous obituarist may well have kicked himself for not having spoken to the friend, Sir Henry Holland, in the first place. “It is told, and I believe the anecdote to be well founded,” Sir Henry wrote, “that Laplace himself [the French mathematician and astronomer], commenting on the English mathematical school of that period, said there were only two persons in England who thoroughly understood his work, and these two were women—Mrs Greig and Mrs Somerville. The two thus named were, in fact, one. Mrs Somerville [was] twice married.” Unlike the obituarist, he also mentioned Mrs Somerville’s children, something no Times obituarist would omit to do today.

At nearly 2,500 words, the sheer exhaustiveness of this volume’s second obituary, that of Harriet Martineau (pp. 18-23), who died in 1876, may have denied readers the chance of adding a postscript – at any rate, none was published. But Miss Martineau’s rare status as one of the comparatively few women of the time to be granted a Times obituary was emphasised when it appeared as the solitary woman’s obituary alongside 54 obits of men in the 1870-1879 volume of Eminent Persons: Biographies Reprinted from The Times, a series of books covering obituaries from 1870 until 1894.

Matters improved for women’s obituaries in the final 20 years of Victoria’s reign. From George Eliot’s (pp. 23-27) in 1880 to Rosa Bonheur’s (pp. 42-44) in 1899, there were seven women’s obits of a quality

meriting inclusion in this anthology. They are substantial pieces, doing justice (or something very close to it) to women who had a major impact on their age – two novelists, an opera singer, a headmistress, a poet, a composer and an artist; four of them British, the rest Swedish, German or French.

Next, on January 23, 1901, came the big one: Queen Victoria’s obituary – too long, alas, to be included here, where we have chosen to reproduce only complete obituaries. Partly because her obituary was almost as much a reflection on the Victorian era as on the monarch herself, “complete” in Queen Victoria’s case means 49,741 words, enough to break the back of any anthology.

Instant coverage on so vast a scale has not been matched by obituaries since. At 14,218 words, Sir Winston Churchill’s obituary was much more succinct. So were those of Baroness Thatcher (10,960 words) and Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother (7,400 words), both included in this book (pp. 437-460 and 330-346).

As with Queen Victoria’s obituary, all three of those later obituaries (and especially that of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother who died at 101) were long in the making. “Times notices may be elaborate composites, updated over many years, sometimes by more than one hand,” says Ian Brunskill, the paper’s obituaries editor from 1999 to 2013. “If it weren’t for the tradition of Times obits being published anonymously, the obituary of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, for instance, would have needed half a dozen bylines, some of them for writers who had predeceased their subject by several years.”

Colin Watson, obituaries editor from 1956 to 1982, was as influential in his time as John Thadeus Delane had been in his. As Watson’s own obituary in January 2001 had it: “He assumed his office at an opportune moment. The mid-1950s saw the beginning of a period of accelerating change in social attitudes… At a time when to be of the ruling establishment or the nobility might to some have seemed a prerequisite for getting one’s obituary in The Times, Watson extended the frontiers of acceptability… An account of so lurid a life as that of the singer, Janis Joplin [pp. 166-167], little calculated to appeal to the traditional readership, was seen as having established the principle of treating the heroes of the new sub-culture on the merits of their impact on the age.”

Seventy years on from Joplin’s death, Ian Brunskill wouldn’t have thought twice about commissioning the obituary of Amy Winehouse (pp. 424-428). A prime concern of Brunskill’s, he says, was to avoid “the tendency to sentimentalise anyone reasonably prominent when they die”. His obituarists, therefore, eschewed excesses of the sort to which Ellen Terry’s 1928 obituary (pp. 96-101) succumbs from time to time – she was, it says, “an actress whose every movement was a poem, whose speech was music, and whose ebullient spirits were constantly caught and guided into a stream of beauty by some natural refinement”.

The Times Great Women's Lives

The Times Great Women's Lives